Automation advantages

Technology solutions offer marine fabricators expanded capabilities, opportunities for greater creativity, and new project and market options.

By Pamela Mills-Senn

Ask Thomas Carlson, manager of Tulsa, Okla., Carlson Design Corp., about his number one competitor and he offers up a surprising response.

“It’s a pair of scissors. Most of our customers have been cutting manually for years. But they’ve also been turning away jobs for years that automation would have allowed them to take on,” says Carlson, whose company provides large-bed plotter/cutters, digitizers, software and vacuum tables to a variety of end users including marine fabricators.

However, he continues, when potential customers do reach out to explore automation, they’re doing so because they’re starting to contemplate the value of their business and if it’s “growable and/or sellable.”

Automation can change the types of jobs marine fabricators are able to handle, such as those requiring repetition, he explains. This can enable them to become, for example, OEM suppliers for a boat dealer, or to take on new projects and reach new markets, such as providing multiple umbrellas for a hotel—jobs that have repetition, high volume and profitability.

Although Carlson says marine fabricators are becoming more open to automation, particularly as they see nearby competitors automating, there’s still some reluctance.

“One of the concerns I hear is that if they automate their cutting, their best cutter will lose his or her job,” says Carlson. “But I tell them that what will happen instead is that automation will allow their most valued people to focus on other areas where they’re most needed. It also allows companies to grow without having to hire additional help. It helps transform the company from a job to a business.”

Changing the paradigm

This rang true for Charles Klein, owner of Dorsal LLC, in Sturgeon Bay, Wis. Klein started the company as a side business in his garage loft 20 years ago. Now he and his five employees work out of a 5,000-square-foot facility and produce “almost anything having to do with boats.” In addition to its marine canvas work, the shop provides awnings and porch curtains.

Klein purchased a Carlson cutter in 2007 with the intention of reducing labor costs and becoming more competitive against multinational corporations manufacturing offshore. This was just the first of his automation purchases.

“After that I knew I had to integrate it into the rest of our product line,” he recalls. “The challenge was to get digital patterns to the cutting machine, and the missing link was the digitizer, which I invested in a year or so later.”

In addition to the cutting machine and the CAD/CAM technology using the Proliner 8 Digitizer, Klein also uses Rhinoceros software, which allows him to do virtual patterning in 3D. These tools have definitely changed how his employees work and what they can do, he says, recalling projects for yacht builders Burger and Palmer Johnson.

“On one 150-foot boat, they wanted a pyramid-shaped sunshade that was straight on the aft side and U-shaped forward. I don’t know how I would have patterned it in paper on plastic, but in Rhino it was easy and it fit the first time. Also, Palmer Johnson used the same dining chairs on 10 of their boats, so it was imperative to get a digital pattern for those 120 covers,” says Klein, adding that he plans on selling Dorsal at the end of this year and starting a CAD/CAM consulting company.

Klein’s discovery that he needed to invest in additional technology wasn’t unusual, says Alan Stewart, vice president of MPanel Software Solutions LLC, a St. Louis, Mo., developer of specialized software for modeling, patterning and engineering of fabric structures and marine covers.

“Sometimes fabricators will purchase one piece of equipment like a plotter/cutter or a digital measuring system believing it to be the most important part of the process,” he explains. “They then struggle to make the equipment provide an efficiency benefit.”

Stewart says while it’s reasonable for companies to purchase this tool to speed up the cutting of their existing templates, “They must pay someone to convert their physical patterns to digital files.” Without CAD, Stewart says, the machine’s functionality is limited to the tools the supplier provides. Its ability to handle custom projects is reduced as well. Adding CAD and digital measuring will help marine fabricators gain “substantial efficiencies” and expand the work they do, says Stewart.

“Once the paradigm shift to digital is made, it’s a much smaller step to add new products, like shade sails, umbrellas, shade structures and awnings,” he explains. “Going digital not only improves efficiency, it also saves money on fabric waste. It’s not unusual to see fabric savings as high as 10 percent.”

Getting started

John Greco, co-owner of J&J Custom Design in Jacksonville, Fla., has been reupholstering furniture for two years and working on developing marine fabrication skills for more than a year. Still in start-up mode, Greco has been looking at automation technology that will help fill in his skills gap—not always an easy task.

“It takes a lot of time to research products because of the specialized area,” he explains. “It forces you to look at things differently—although since I’m new to the field, I didn’t have to ‘un-think’ the way things are done. Having a background in technology, I know finding the right technology has the potential of being a great help.”

Some of the products he’s reviewed include Prodim for patterning, PhotoModeler and iWitnessPRO™ for digitizing patterns, and ProSail for plotting a pattern onto fabric and cutting. One of the key takeaways from his still-ongoing research is that strong manual skills are a must before converting to automated processes.

Amy Poe, co-owner of Wyckam LLC, a Portland, Ore., provider of solutions for projects requiring industrial sewing, says she began by identifying and then automating her most time-consuming process.

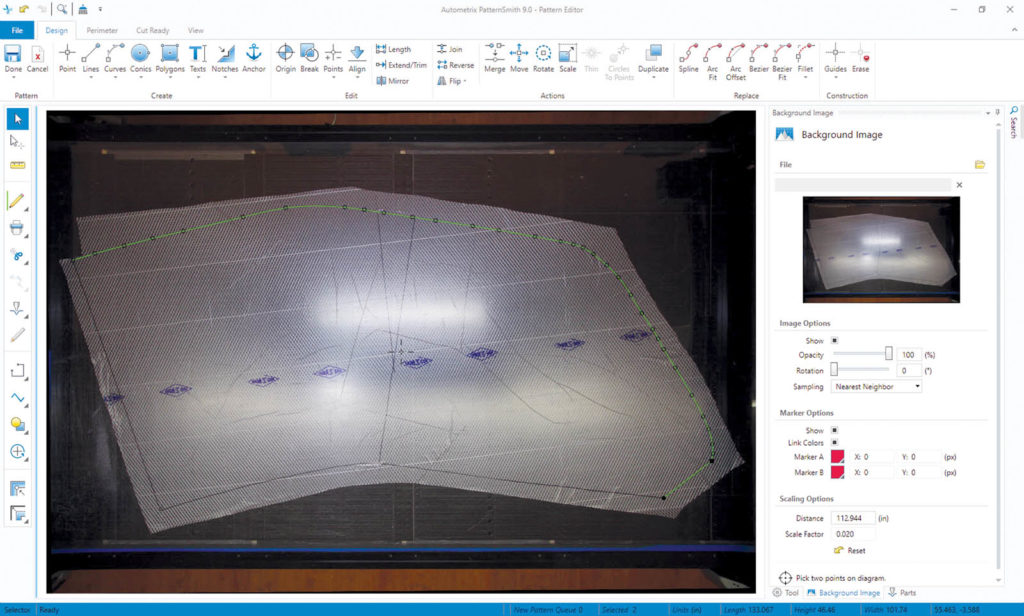

“Once that solution is in place and saving you time, look for the next business process to improve,” suggests Poe, who purchased an Autometrix cutter, a digitizer and CAD software in 2007. “Continued improvement will eventually reduce your costs, streamline your operations and improve your bottom line.”

Start with 2D

The learning curve for certain technology can be steep, even with supplier support. For example, if a marine fabricator has never used any form of automation before, taking a conservative approach can make more sense and ultimately deliver better results, says Carlson.

“If you buy a Carlson plotter/cutter, CAD program, 3D digitizer and Carlson nesting software all at once, you have to learn CAD, 3D digitizing, a new process for making boat covers, the plotter/cutter, nesting software and basic computer file organization all at once,” he explains. “But if you start with 2D, it allows the operator to learn how to use CAD, nesting and the plotter/cutter while following a process similar to manual patterning.”

Taking this approach will make integrating the tools into shop operations less stressful and easier on employees, encouraging buy-in, Carlson says. Plus, the business will start realizing a swifter ROI. “The ROI on a 3D solution that isn’t properly implemented is never,” says Carlson.

There’s a huge difference between 2D and 3D, says Klein, describing the switch from the former to the latter as challenging.

“It pretty much took a winter season for me,” he says. “It’s the difference between drawing and sculpting. You really have to think in 3D. Instead of drawing a line from a to b, you’re extruding objects, poking holes in them, stretching virtual surfaces between bows, and through trial and error, making some educated guesses about stretch and sag.”

Anxiety over learning CAD is one reason why companies resist transitioning to digital, says Stewart, who suggests those completely unfamiliar with the tool consider hiring someone. “This can be part-time to start; there are plenty of CAD students eager to earn some money,” he says. The rest of the equipment involved in the digital process isn’t hard to learn or operate, Stewart adds.

Probably the biggest obstacle is resistance from employees uncomfortable with change and/or technology, says Gary Unitt, who works in software and hardware solutions for Autometrix Inc., a Grass Valley, Calif., provider of automated cutting solutions for the industrial fabrics industries. To quell concerns and get everyone on board, he says managers need to champion the technology and support employees through their growing pains as they make the transition. Pairing the equipment with the right employee is also critical, he adds.

“Decide ahead of time what projects will use the automation first,” Unitt advises. “Start thinking about who may be best suited to operate the new technology—you may need to look outside your company. Keep the pressure low so employees have room to learn and become comfortable. And don’t fall into the trap of ‘I can do it faster the old way.’ Speed comes with time and repetition.”

Pamela Mills-Senn is a freelance writer based in Long Beach, Calif.

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG