Simplify employee training and patterning

Simplifying employee training and complicated patterning

By Broc Wodzien

Grand Traverse Canvas Works, in Traverse City, Mich., has had many wonderful employees over the past 30-plus years. Our shop has grown from just my mother, Mary Wodzien, using the skills she learned at her stepfather’s canvas shop, to a staff of 16 employees. Growing and maintaining our staff involves a lot of training and skill development.

Since few new employees have experience in our profession, this starts as a teacher/student dynamic and transitions into a collaborative process as they gain experience. This process is not always smooth, and it challenges our assumptions of our work. Training new fabricators gives your company the opportunity to critically reevaluate the techniques you employ on a daily basis.

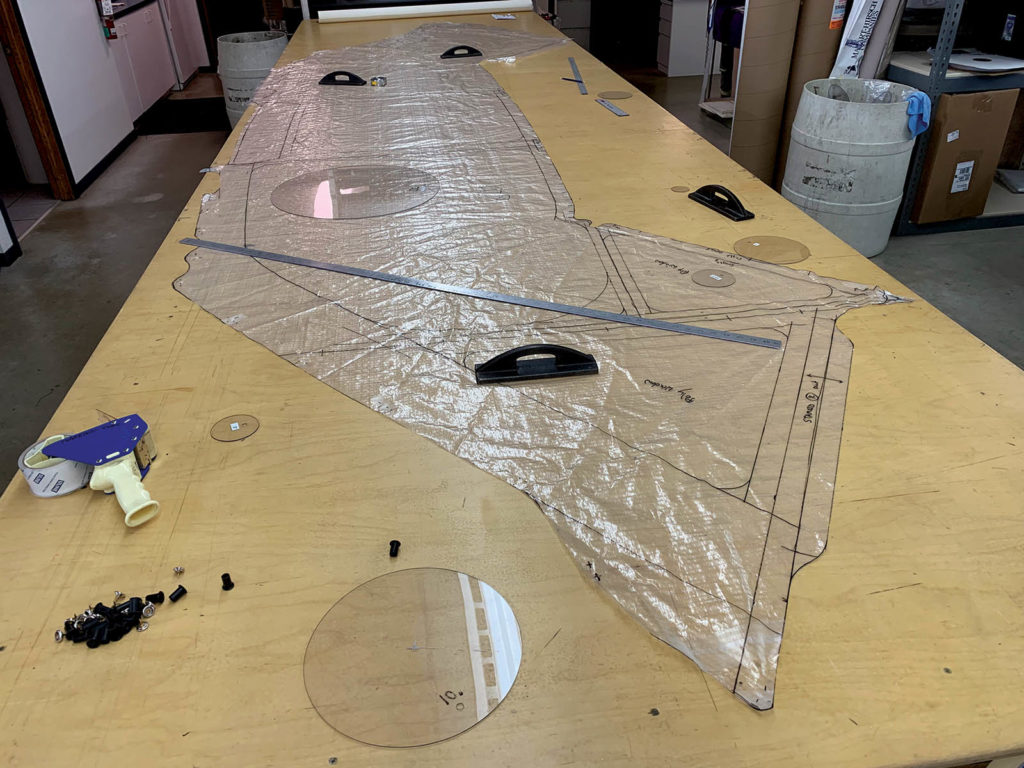

In this article, I will discuss how we teach and learn, as well as some of the tools and techniques we can give new members of our profession to set them up for success. I’ll also examine some of the complex shapes that can stymie new and experienced fabricators alike, and the tools we can use to break projects into manageable pieces, prototype on the fly, and turn out nicer looking products more quickly.

Where to start training

Our new employees come with very little experience or competency in marine fabrication, but they often have tangential knowledge from a hobby or similar work experience. In psychology-speak, we would call this “consciously incompetent.” They don’t know or understand how we do what we do, but they recognize and value the skills required.

As new fabricators gain experience and learn new techniques, they move toward “conscious competence.” They understand how to make something, but it takes concentration and effort to execute their new skills. On the other end of the spectrum, experienced fabricators are “unconsciously competent.” Designing and fabricating are second nature to them, and they have a large, unconscious toolbox of experience to rely on.

The challenge when something is second nature is explaining it. Similar to when a child asks how you tie your shoes, we have to turn something we no longer think about into actionable steps. It’s easy to fall back on the “This is the way I’ve always done it” explanation, which forces new team members to memorize everything without understanding it. But it is more effective to break things down into teachable components.

Establish shop standards

Most fabrication teaching falls into two categories: techniques and design elements with concrete reasons, and those that are based on personal or shop preferences. It’s important that both types are taught as clearly and consistently as possible. Concrete reasons for product designs are generally based on ease of fabrication, cost, durability, how it looks and how it works. Unfortunately, we rarely get the time or budget to hit each of these perfectly. Teaching your staff how to prioritize these things based on what the customer wants and what you want to put your label on is very important.

Being clear when something is a shop preference is important as well. A lot of small details are preferences that benefit from consistency since they don’t have hard reasons behind them, and there’s a wide range of functionally right answers. An example is the border width on an enclosure panel. Since 1¼ inch, 1¾ inch or 2 inch are all functionally viable answers, choosing one as the shop standard eliminates the need to question it on every job.

To establish shop standards, we fabricate small example pieces that give us foundational building blocks to refer to. This holds us accountable, instills confidence in our decisions, gets answers faster when we’re unsure and allows us to repeat good ideas when there might be months between similar projects. Being able to pull small examples down and have new team members duplicate them gives new fabricators a safe way to learn a new skill and eliminates the confusion of trying to describe it. If a picture is worth a thousand words, a sample piece is worth 10,000. Our wall of sample pieces continues to evolve as we try new things and are faced with new projects.

Broc Wodzien grew up in his parents’ canvas shop, Grand Traverse Canvas Works. He spent 30-plus years surviving falls off patterning tables and sliced fingers on cut tubing, and spent many summers helping install covers at marinas in northern Michigan. He reentered the profession in 2012 and has helped systemize the shop’s 40 years of history, know-how and excellence.

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG