Choosing automated marine fabrication systems

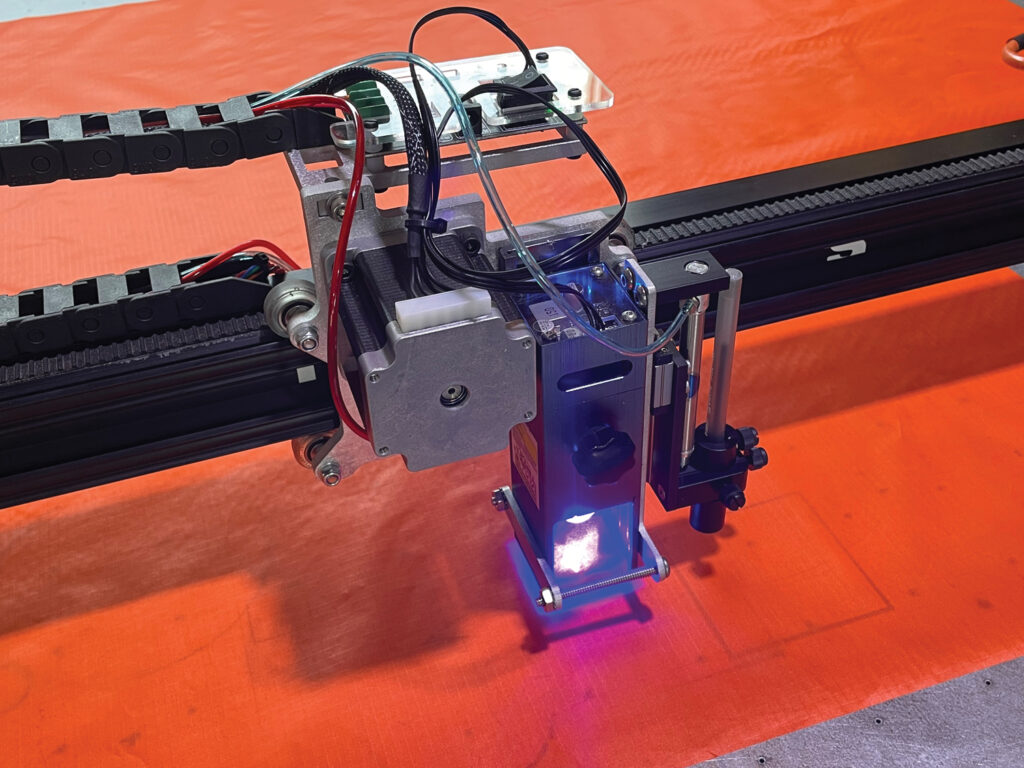

Perhaps someday, thanks to artificial intelligence and who knows what else, marine fabricators will just need to envision a new boat cover in their heads and it will appear. In the meantime, fabricators who want the most modern operations are increasingly turning to the use of digital plotters and cutters, state-of-the-art technology tools that mark and cut fabric with accuracy and precise repeatability.

“The big thing overall is that these tools give you efficiency,” says Jeff Newkirk, MFC, owner and principal designer at Precision Custom Canvas Inc., in St. Catharines, Ont., Canada. “And efficiency is not just cost savings, but time savings as well—which is always an ongoing battle for small businesses and small business owners.”

Going digital was “a complete game-changer,” according to Darren Arthur, a former fabricator who in the past two years launched Nautitech Solutions Inc., a consulting firm that advises fabrication operations and digital design services.

“I come from an engineering background, and I saw other industries that were integrating technology,” says

Arthur. “Larger marine shops had done it. But when I purchased my first plotter and cutter and table, I only had one other person working for me, and it was a little intimidating.”

Establishing standards

“You no longer have handmade patterns you can touch and feel. Capturing your data is different, and there’s a learning curve there,” says Arthur. “When you do design in CAD, you can’t design it differently each time; you need some sort of standard. You don’t want to reinvent the wheel in each instance.”

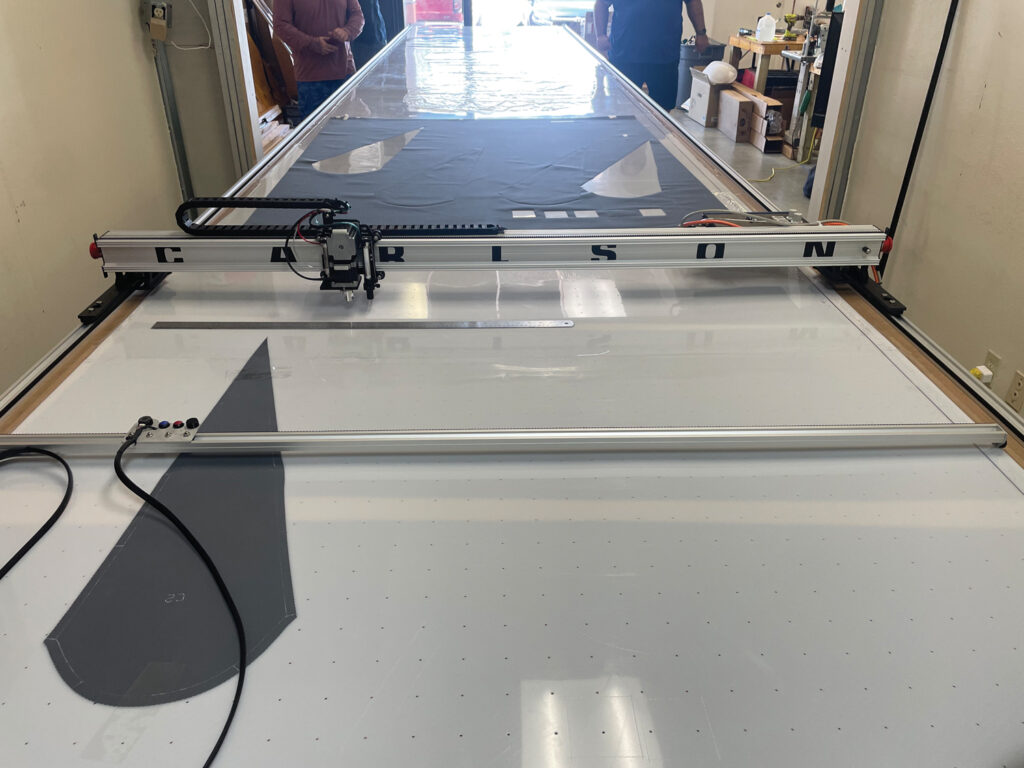

Thomas Carlson, manager of Carlson Design in Tulsa, Okla., has been selling CNC fabric plotters/cutters for more than 15 years, with his father, who was a pioneer in the industry and founded the company in the late 1980s. “My father was working in a sail loft while finishing his master’s degree in mechanical engineering,” says Carlson. “He noticed the tedious process involved for sailmakers to plot a list of Cartesian coordinates on fabric by hand. He thought, ‘I can make a machine to do that,’ and our first plotters were born. Sailmakers were CAD pioneers, using computer design in the fabric world.”

When Carlson is talking with fabricators who want to make the switch to digital, he says they often want to focus on whether digital processes will help them maintain their high-quality competitive advantage.

“Most guys pride themselves on the quality of what they are making—they determine that’s what separates them from the other guy,” he says. “‘You can bounce a quarter off my cover, where the other guy’s cover fits loosely or seams are not done correctly.’ We never want anyone to sacrifice quality, but if everything you make is custom, the discussion of automation doesn’t begin with quality. Instead, we shift the conversation to see if there are any products or processes that could benefit from repeatability or scalability. Identifying a certain task like this is a great place to start and a way for automation to get a foothold in an all-custom shop.”

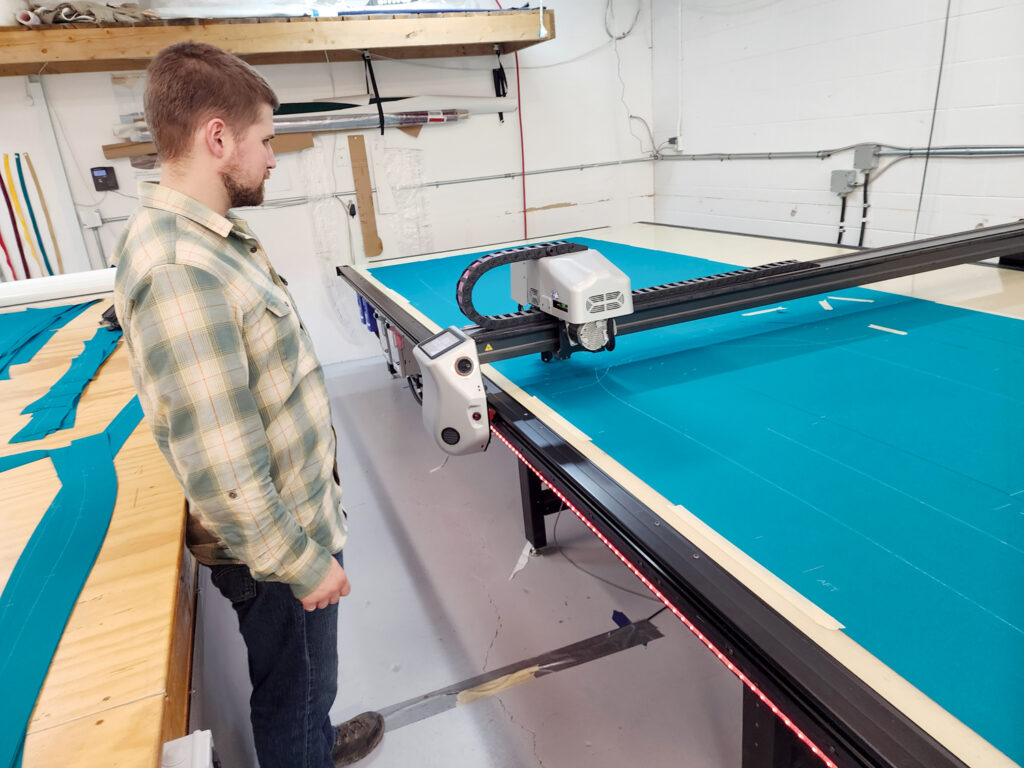

“We work with the customer to capture how they are doing things now and then show them how to do it on the computer,” says Gary Unitt, product manager at Autometrix Inc., which makes automatic cutting machines and the software needed to run them from a facility in Grass Valley, Calif. “You need to set yourself up for success. The key is to start with simpler projects, trying to go through the same process you use now but using CAD to do your design work. Then you work your way into the more complex and difficult projects. You will quickly see how this process can save time and money.

“We start the training process before the machine ever arrives,” adds Unitt. “We want our customer to be comfortable with the software, so that by the time the machine arrives and is set up, you have patterns created and ready to go. It depends on the user, but we usually say it takes a couple of months, using the machine and software daily, to ramp up.”

Commitment to change is key

“The biggest challenge is that you really have to be committed to the change,” says Amy Denning, vice president of North American Sales at Eastman Machine Co., which has been in business in Buffalo, N.Y., for 135 years and has been producing automated systems since the 1990s. “You have to get over that hump with regard to using software and the knowledge that’s required for a different way of creating patterns.

“Teaching people how to run our machine is the easy part,” explains Denning. “The transition from manually creating patterns to doing it digitally is the more difficult task. We make sure our customers are properly trained and supported to ensure they are comfortable with the processes.”

“We also have partners such as Prodim that teach the fabricators how to go out on a boat and create digital patterns.

“But if a place is not fully committed to making a change, the transition can be difficult,” Denning says. “The companies that provide the technology are committed to the customer, but we also need that commitment from the customer that they’re fully on board.”

According to Carlson, his company’s training includes the joke that the new machine will be the newest employee named Carl. “Carl shows up on time every day and always cuts exactly what you tell him to cut,” he says. “Learning to tell Carl what to do is the challenge and the real focus of our training. We start out telling him to do simple things and not the world’s most complex project. In time he’ll be cutting everything.”

“The larger the shop, the more challenging it can be, because you are implementing changes on a wide scale,” says Arthur. “You also have to look at what the culture is. Are people open to change, do they embrace the change, or they are afraid of change? Learning an entirely new way of doing things can be uncomfortable but ultimately makes the job easier. It’s the change that can be hard. People need to be change-agile in today’s work environment. ‘We’re changing this to improve, not to make it more difficult.’”

Success can depend on how a fabricator promotes the change, Arthur adds. “Help employees understand why you are making the change—it benefits them, it’s more profitable, there’s no more crawling around on hands and knees, it’s easier on the body. You can be a lot more profitable and pay people better.”

Choose the right model

The biggest decision fabricators face when deciding to go digital is what specific type of plotter/cutter might be right for their shop. Most manufacturers don’t have more than a handful of models, but each is made for specific purposes. The equipment-makers work with fabricators to determine the right choices.

If fabricators have 60-inch-wide rolled goods, and their current table is 24 feet long, that’s a good starting point for sizing the automated cutting table, says Unitt. There are two types of tables, he explains—a “static” table, which is a table that is a fixed size. The operator covers the table with fabric, the machine cuts the patterns, and then the operator picks them up and starts again.

“The other, which is gaining a lot of traction and becoming more and more popular, is a conveyorized table,” he says. “This has a fixed-width table, and the fabric moves on a conveyor belt. Fabric feeds on one end of the machine and cut parts come off the other end. You’re limited only by the length of the fabric on the roll—and you can save a lot of space in your shop.”

Obsolescence is not an issue

Technology is well known to quickly become obsolete, which may make prospective fabricators wary, but obsolescence doesn’t seem to be a major issue in this technology.

“Our company has been manufacturing cutting solutions for 135 years and we strive to support our older models as long as we can,” says Eastman’s Denning. “When we introduce new models, we offer a trade-in program and offer to buy back or upgrade the older system, allowing our customers to upgrade to the latest model and technology.”

“We have machines out in the field that are 20-plus years old,” adds Unitt. “Most machines will have at least a 15-year life span due to changes in electronics, and software gets constantly updated. You don’t have to worry about being outdated in six months.”

So, if a shop wheels in a bunch of shiny new cutting machines, do they throw away the scissors? “For little covers and accessory things, it doesn’t make sense to digitize them and then go into CAD,” says Newkirk. “If it’s something small or a one-off, it might even take longer to do it using the CAD process. You need to recognize that hand skills are not obsolete—and they are important.”

Jeff Moravec is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn Park, Minn.

SIDEBAR: Less work, more time

Most businesses that decide to streamline their processes do so for one reason—to bring in more business. While having time for new customers was important to Jeff Newkirk, MFC, when he automated processes at Precision Custom Canvas Inc. in St. Catharines, Ont., Canada, there was much more to it.

Having a plotter/cutter allows Newkirk to have his CAD designer run a cutting table, even though he’s never worked with scissors before: “I can get precise cutting out of someone who has never honed scissor skills, and that takes the pressure off me and my other sewers. We’ve developed more streamlined approaches.

“When a shop is operating more efficiently, you have two options,” says Newkirk. You can grab more work, or you can maintain your level and actually work a little bit less. We’re working on increasing our volume but not replacing all the hours.

“There’s a seasonality to our business. In the spring there is always a crunch,” he says. “But we can end the overtime earlier than when we were doing everything by hand, so the staff can enjoy summer and we can all enjoy life. It just makes sense.”

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG